I want to say to you, read the book, the Pearl of Great Price, and read the Book of Abraham. The Pearl of Great Price I hold to be one of the most intelligent, one of the most religious books that the world has ever had; but more than that, to me the Pearl of Great Price is true in its name. It contains an ideal of life that is higher and grander and more glorious than I think is found in the pages of any other book unless it be the Holy Bible. It behooves us to read these things, understand them: and I thank God when they are attacked, because it brings to me, after a study and thought, back to the fact that what God has given He has given, and He has nothing to retract." - Levi Edgar Young, Conference Report (April 1913), 74

"...it must be evident to all who seriously consider the matter, that if the Book of Abraham as given to us by Joseph Smith be true, it must have been translated by a greater than human power." - George Reynolds, The Book of Abraham: Its Authenticity Established as a Divine and Ancient Record (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1879), 4

Saturday, October 7, 2017

Thursday, October 5, 2017

LDS Perspectives Podcast with Matthew Grey

A transcript of this interview is available here.

Wednesday, March 29, 2017

Book of Abraham in Wilford Woodruff's Journals

November 25, 1836 (WWJ 1:106-107)

Monday, March 27, 2017

Book of Abraham in the Journal of Discourses

Orson Pratt (August 29, 1852), JD 1:57-58

Monday, March 6, 2017

Richard Bushman on the BoA Translation

In light of Joseph's language study, the Egyptian grammar appears as an awkward attempt to blend a scholarly approach to language with inspired translation. Like Abraham, Joseph wanted to be one who "possessed great knowledge." He began his career as a prophet by translating gold plates inscribed in "reformed Egyptian." As late as 1842, he worked on the translation of papyri from an Egyptian tomb. The allure of the ancient comes through in the revelation to Oliver Cowdery about "those ancient records which have been hid up, that are sacred." Beyond the Book of Mormon people, other Israelites had kept records that would flow together in the last days. The sealed portion of the gold plates was yet to be revealed, and revelations to sundry others had generated caches of records, all part of the Lord's work, all to be recovered in time. Translation gave him access to the peoples of antiquity.

Full of wonders as it was, the Book of Abraham complicated the problem of regularizing Mormon doctrine. The Doctrine and Covenants was meant to stabilize Mormon beliefs, but in the very year of its publication, the papyri rode into Kirtland in Michael Chandler's wagon, bringing news of Abraham from the tombs of Egypt. Every attempt to regularize belief was diffused by new revelations. Who could tell what would be revealed next--what new insight into the patriarchal past, what stories of Abraham, Moses, or Enoch, what glimpses into heaven? Joseph himself could not predict the course of Mormon doctrine. All he could say he summed up in a later article of faith: "We believe all that God has revealed, all that he does now reveal, and we believe that he will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the kingdom of God."

_________________________

Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 290-293

Monday, February 13, 2017

Notes: Book of Abraham Revelations before Book of Abraham Translation

___________________________

1 W.W. Phelps, "Letter No. 8," June, 1835, Latter Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate 1/9 (June 1835):130; Phelps also wrote, "I am truly glad you have mentioned Michael, the prince, who, I understand, is our great father Adam," which corresponds to temple-related doctrine even before the Kirtland temple was finished, much less the Nauvoo temple.

Friday, January 6, 2017

LDS Perspectives Podcast with John Gee

A transcript of this interview is available here.

Wednesday, December 21, 2016

Notes: Greek Borrowing in Ptolemaic Egypt

___________________________

1 Robert Steven Bianchi, "The Cultural Transformation of Egypt as Suggested by a Group of Enthroned Male Figures From the Faiyum," Life in A Multi-Cultural Society: Egypt from Cambyses to Constantine and Beyond, ed. Janet H. Johnson, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization No. 51 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1992), 15

Thursday, November 17, 2016

1835 - Improvement Era (1942) - W.W. Phelps

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Sunday, August 28, 2016

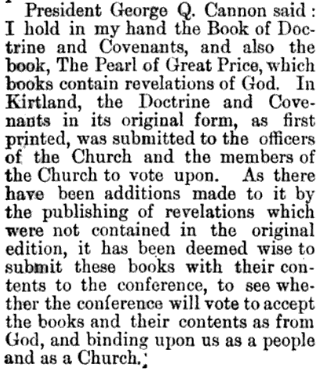

Pearl of Great Price as Canon - Millennial Star - Nov 15, 1880

Orson F. Whitney on Abraham and Bishop Spaulding

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

Notes: Egyptian (Auto)Biography

Monday, August 15, 2016

Notes: "The Disjunction of Text and Image in Egyptian Art"

"It is a significant point in this example that the small number of elites who could read would not have interpreted the monuments of Ramesses II in the same way as the vast public. For this last group the temples were in any case distant and restricted centers of authority, royal and religious. Nonetheless a complete message was communicated to both audiences. We cannot estimate with any certainty the degree to which the owner of a monument depended on the separate and combined messages of art and inscription. We are safe, however, in assuming that all those who viewed a monument did not take away the same message....Indeed, this dissonance in text and image can be found on nearly every inscribed object and must assert that the function of text with image was other than caption or explication."5

Notes: Vignette Alignment with Text

Malcolm Mosher, Jr., "An intriguing Theban Book of the Dead tradition in the Late Period," British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 15 (2010): 124

Notes: Papyri Comprised of Unrelated Texts

___________________________

Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of Ancient Egypt (West Sussex, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 11, 146, respectively

Friday, August 12, 2016

Notes: Abrahamic Traditions

______________________

Ben Zion Wacholder, "Pseudo-Eupolemus' Two Greek Fragments on the Life of Abraham," Hebrew Union College Annual 34 (1963), 96; scholars are uncertain as to whether Pseudo-Eupolemus' fragments were written in Palestine or Egypt; see John J. Collins, Between Athens and Jerusalem: Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Diaspora, 2nd ed.(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), 49